http://www.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/industry-news/energy-and-resources/a-railway-to-arctic-riches-economic-boom-environmental-threat/article4259449/?page=all

http://www.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/industry-news/energy-and-resources/a-railway-to-arctic-riches-economic-boom-environmental-threat/article4259449/?page=all

A handful of people shuffle into the community hall in Kimmirut, Nunavut, a tiny outpost on the southern coast of Baffin Island. It’s early December, and the small group shakes off the cold winter air and settles into folding chairs to hear a presentation about something completely foreign to Baffin Island – a railway.

“I have never seen a railway before,” a woman named Joannie tells the gathering, according to minutes of the meeting. “Could you give a better idea of what the train will look like?”

Nobody else has seen a railway on Baffin Island either. No one has built one this far north, anywhere. But now – thanks to an insatiable global demand for minerals, and climate change that has opened up northern shipping routes – a rail line across part of Baffin Island is about to become a reality.

It’s also a sign of things to come. Places like Baffin Island have always held a treasure trove of minerals, but low commodity prices, coupled with the high cost of operating in the Arctic, left many deposits undeveloped. With prices for nearly every mineral now soaring, however, mining’s last frontier has become financially viable. And with temperatures climbing because of global warming, mining in the Arctic has become logistically possible as well, because sea lanes stay open longer due to thinner ice and railways can operate year round.

In the past year, two iron ore mines in Norway’s far north have been re-opened after being abandoned for 14 years and there are plans to open an iron ore mine in northern Sweden. Greenland has been overrun with dozens of mining companies eager to dig into rich deposits of uranium, zinc and rare earth minerals that have been uncovered by melting ice caps. Russian cargo ships have started plying the icy Arctic waters carrying tonnes of minerals from mines in Siberia to Rotterdam.

The people in Kimmirut and several other communities across Nunavut are already getting an idea of what’s about to happen in Canada. For months, they’ve been poring over plans for a giant iron ore mine at Mary River, on the northern reaches of Baffin Island and roughly 1,000 kilometres northwest of Iqaluit. It is easily among the most ambitious mining ventures ever undertaken in the Arctic, and an illustration of the lengths to which companies are going to find the resources to build the world’s emerging economies.

The mine itself will be an open-pit operation spanning more than two kilometres across the top of a small mountain. There will also be a townsite with an airstrip capable of handling commercial jets, and a deepwater sea port fit for 10 ice-breaking cargo ships roughly 15 times larger than any vessel currently sailing the eastern Arctic.

Linking everything together will be a 149-kilometre railway that is designed to carry trains stretching more than one kilometre in length from the mine site to the port. The mine, the trains and the ships are intended to operate every day for 21 years and move 18 million tonnes of iron ore annually to ships that will take the metal to blast furnaces in steel mills across Europe.

The impact on Nunavut will be profound. The mine is expected to triple the territory’s annual gross domestic product growth rate and provide nearly $5-billion in tax revenue and royalties to the territory over the life of the project. It will create more than 5,000 direct jobs, many more indirect positions and offer training opportunities in an area of the country where four out of every six people live in social housing and life expectancy is 10 years lower than the rest of Canada.

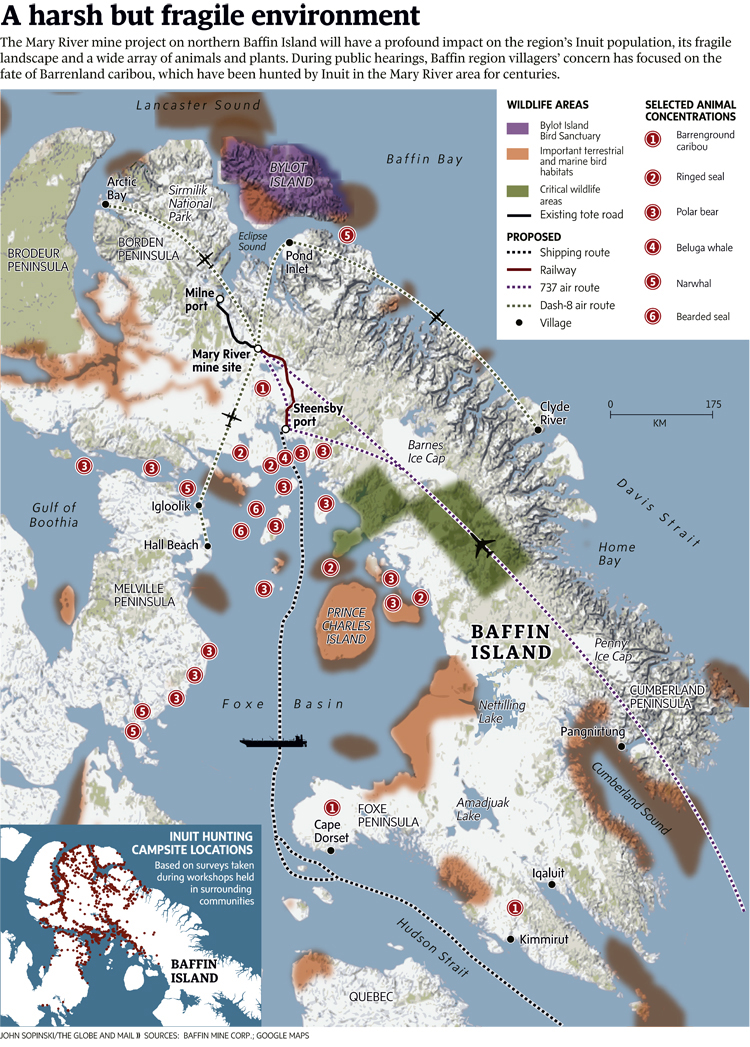

But there will also be consequences. The mine will leave untold scars on the natural landscape and cut into the fragile permafrost. It will affect caribou migration, disturb walrus populations and have an impact on seals, polar bears, beluga whales, foxes, ermines, lemmings, hares and narwhals. It is an age-old tension – jobs and economic development versus the environmental costs – but one that is about to be felt in new ways in northern communities around the world, and particularly in Canada.

Mining in the north isn’t new; there are other projects in Nunavut. But it has never been attempted on this scale before. Iron ore is all about volume, and by that measure, no other mining project in Canada’s North comes close to Mary River. The nearest comparison is the Raglan nickel mine in Northern Quebec, a key holding of Anglo-Swiss giant Xstrata PLC. Raglan produces about 1.3 million tonnes of nickel annually, making it a large-scale nickel operation. But that’s still less than 10 per cent of the product that will hauled out of Mary River every year.

Residents in places like Pond Inlet, 170 km from the proposed mine, are wrestling with the project. “This project is large, very large,” said Colin Saunders, the town’s economic development officer. “The amount of jobs and opportunities that will be available to the High Arctic residents are going to be significant, very significant.

“But there’s a trade-off and you have to balance the jobs and the contracts with the environmental impacts.”

The evolution of a mine

Just about everyone in the mining world has known about the iron ore at Mary River for decades. Mining it has been a dream ever since Murray Watts, a legendary Canadian prospector, climbed into a beat-up Cessna in July, 1962, to scout around the northern part of Baffin Island.

No one took the trip seriously at the time; mining industry players figured that finding anything in the barren setting was hopeless. But Mr. Watts had long believed in the riches of the north and he had been exploring the northeastern Arctic for 30 years. After a few more trips that summer, Mr. Watts found four iron ore deposits south of Pond Inlet. The site was named Mary River by Europeans, but it had been a meeting place for Inuit hunters for centuries.

The richness of the deposit astounded even Mr. Watts. The iron content ranged from 65 to 70 per cent. That’s so pure that the ore can be picked up, dusted off and tossed into a blast furnace. And yet, despite the attractiveness of the find, no company had the financial wherewithal to mine it.

Mr. Watts died in a car crash in 1982, and four years later, the site ended up in the hands of Baffinland Iron Mines Corp., a small Toronto-based company. But development costs were just too high and the project was shelved. Interest was reignited in 2004, when Baffinland went public and raised enough money to cover some testing and surveying at the site. The results confirmed the remarkable quality of the find and that it was the one of the largest undeveloped iron ore deposits in the world. By 2007, the company had calculated that a mine would cost more than $4-billion, far beyond the ability of a small player like Baffinland to raise, especially with a global credit crunch starting to unfold.

By the middle of last year, financial markets had recovered and the price of iron ore was climbing to record levels. Suddenly Mary River was in hot demand and Baffinland was the target of a global bidding war that pitted a U.S. private equity fund against Luxembourg-based ArcelorMittal SA, the world’s largest steel maker. After battling for months, and jacking their bids from 80 cents a share to $1.50, the two sides called a truce and made a joint offer last January worth more than $500-million. The takeover closed in March.

Now, with ArcelorMittal’s backing, Baffinland was finally ready to forge ahead with its dream mine at Mary River, at a price tag of $4.1-billion.

There was never any doubt the project would be expensive and gigantic. But material filed at the Nunavut Impact Review Board – 10 volumes of documents spanning more than 5,000 pages – offer a unique perspective on just how complex it is.

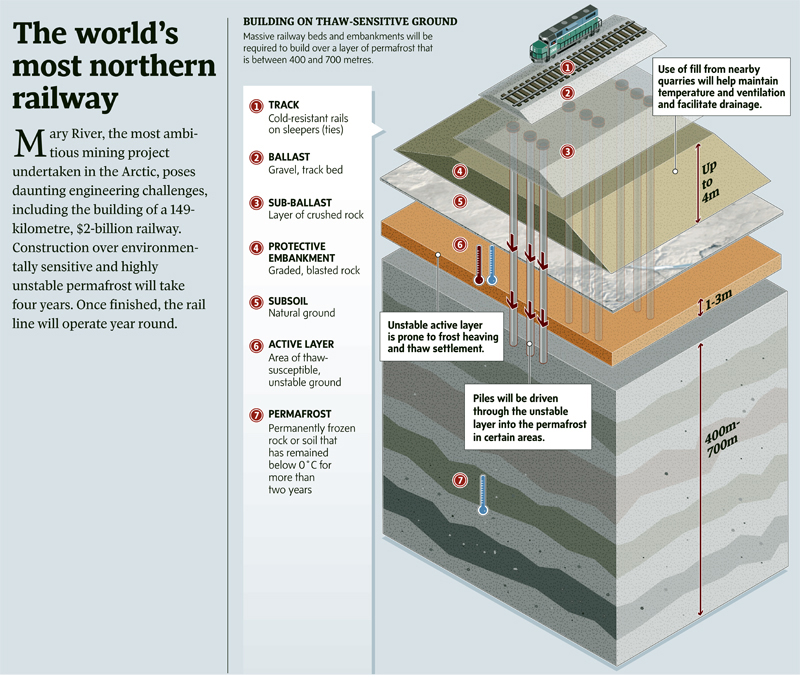

The rail line is the trickiest part. It will cost nearly $2-billion, or up to $13-million per kilometre, and take four years to build. Construction will require more than 1,000 workers, divided into four teams camped out along the route. The track will run from the mine site to a new port at Steensby Inlet, along the western side of central Baffin Island. Mapping the route took years because of the difficult terrain; the rail line will require 31 bridges and two tunnels, including one measuring 1.3 kilometres.

Building all that would be hard enough anywhere, but the constant cold in the Arctic means many sections of the line, including the bridges, will have to be pre-assembled and then shipped in. But even with global warming, regular transport ships still have to travel mainly in summer, making logistics a potential nightmare. “You only get one chance a year to get material up there,” said Ron Hampton, the project director. “It forces you to be very efficient at your planning.”

Permafrost poses another challenge. Baffin Island is covered with continuous permafrost about 400 metres deep. But the surface layer, about three metres thick, is subject to seasonal freezing and thawing. The train track will be set on an embankment measuring up to four metres in height and made from crushed rock to provide stability over the fragile ground. Supports for bridges will be driven into the bedrock to ensure they keep stable if climate change alters the surface.

Once the track is built, the railway will be in constant use. Along with hauling iron ore, the line will provide a passenger service for employees and transport supplies to the mine site. Each train will be at least 110 cars long and rumble down the track at up to 75 kilometres per hour. The total rail fleet will include 367 rail cars and 11 locomotives, especially made to withstand the cold.

The port at Steensby Inlet will handle year-round voyages back and forth to Europe, with one ship moving through the icy waters every 32 hours. The company’s shipping fleet will include 10 ice-breaking cargo vessels, some measuring 329 metres in length and having five times the carrying capacity as ships used at the Raglan mine. Most are expected to head to Rotterdam, a round-trip voyage that will take up to 45 days in winter.

A cultural divide

Baffinland officials have taken the proposal to communities across the region for months, with several more meetings slated in coming weeks. It hasn’t been easy. Barely 5,400 people live within 400 kilometres of the mine, and their lifestyle is different even from other parts of Nunavut. Roughly 41 per cent of the population is under the age of 15 and 40 per cent of families earn less than $10,000 annually. Many people live off the land, hunting herds of caribou that roam directly across the route of the railway.

Some meetings attracted just five people, many of whom spoke only Inuktitut. But passions ran high and opinions were sharply divided about the project. The regulatory filing includes nearly 700 pages of comments from residents and minutes from several community meetings.

“Our ancestors brought us here through their survival on country food, with no white man,” one man said. “I might behave like a white man, but it is my father’s words I use when I go hunting. I don’t know computers and can’t speak English, but I am passionate about our knowledge.”

“Thank you for trying to help us get more jobs, but the Inuit and white are different,” another man said. “They should be treated equally. When white man is trying to be on top, they don’t like Inuit. Don’t come here then, if you don’t like Inuit.”

Officials at Baffinland insist the project will respect the local culture and protect wildlife. They point to other northern mining projects that have not disrupted caribou and provided badly needed opportunity. The Mary River project “has the potential to provide significant benefits to the north and we’re just working through a process now that we need to get through and reach a point where we can develop it,” said Greg Missal, Baffinland’s vice-president of corporate affairs. If all goes well, he added, construction could start in early 2013.

But convincing people like George Qallaut, who lives in Igloolik which is across from the Steensby Inlet, won’t be easy. During one public meeting, Mr. Qallaut stood up and spoke about the 4,000-year history of the area, and about the dramatic changes in landscape the project will cause.

“The people of Igloolik and Pond Inlet have for centuries met at Mary River during the summer hunting caribou,” he told the group.

“An elder present at this meeting got his first caribou at Mary River. Two mountains will be gone in 25 years. Part of their identity will disappear. How can you compensate for this?”

The Globe and Mail

Published

Last updated